With her eight-day-old baby cradled in her lap, 24-year-old Saptami Mondol sat on a tarpaulin sheet laid across the dusty floor of a classroom inside Parlalpur High School. The building, located in West Bengal’s Murshidabad district, has been transformed into a temporary shelter after communal violence erupted over the newly introduced Waqf law last week.

Saptami is one of nearly 400 displaced men, women, and children now seeking refuge in the school. Her village, which lies across the Ganga River or 60 kilometers away by road, remains a distant and terrifying memory. “We have become refugees in our own land,” she said with tears in her eyes. “We may never return. What if they attack us again?”

The violence that shattered the lives of these villagers has already claimed three lives. Among the victims were 72-year-old Hargobindo Das and his 40-year-old son Chandan Das, who were reportedly dragged out of their home by a violent mob and killed. The incident has left a deep scar in the hearts of the people, many of whom witnessed the chaos unfold before them.

While authorities claim the situation is under control—with over 200 arrests made—those who fled their homes live in constant fear. “On Friday, the mob set fire to our neighbour’s house and hurled stones at ours. We were hiding inside, terrified,” Saptami recalled. “In the evening, after the mob dispersed and the BSF began patrolling, we fled.”

Her mother, Maheshwari Mondol, described the harrowing journey they made. “It was dark when we reached the ghat. We boarded a small boat and crossed the Ganga. On the other side, a kind family sheltered us for the night and gave us some clothes. The next day, we came here.”

As Saptami narrated her ordeal, she looked down at her baby, whose tiny body had developed a fever during the river crossing. “We had nothing—no food, no clothes, just what we were wearing. Everything we have now has been given by others,” she said.

The displaced families taking shelter at Parlalpur High School hail from areas such as Suti, Dhulian, and Samaherganj—all of which were caught in the epicenter of the violence. Inside the classrooms, school benches have been cleared to make room for bedding. Tarpaulin sheets cover the floors, and local villagers, along with district authorities, are working tirelessly to provide food, clothes, and medical assistance.

56-year-old Tulorani Mondol, a widow from Dhulian, said, “My house was set on fire. We want a permanent BSF camp in our area. Only then can we think of going back.”

Inside a classroom on the first floor, 30-year-old Pratima Mondol from Lalpur recounted her trauma. “We were hiding on the terrace as the mob ransacked our home. The next evening, we crossed the river with my one-year-old. We didn’t get the chance to carry anything. What happens when the police and BSF leave? Who will protect us then?” she asked.

40-year-old Namita Mondol, a resident of Sabjipatti in Dhulian, sat quietly in a corner of the classroom with her 18-year-old son. “We left everything behind,” she said. “I don’t know when or if we will go back.”

The local community has shown remarkable solidarity in helping those affected. Reba Biswas, 57, and nine other women from the area cooked lunch for the displaced families. “We sheltered many of them in our homes on Friday night and then brought them here,” she said.

Dr. Prasenjit Mondol from Kumbhira Primary Health Centre, who is currently posted at the shelter, confirmed the presence of vulnerable individuals in need of medical care. “There’s a pregnant woman here, and another woman who was due for delivery has been shifted to Bedrabad Rural Hospital,” he informed.

The administration has provided food, clean drinking water, and essential supplies to the shelter. “We serve rice, lentils, potatoes, and eggs to the adults. Infants are given baby food and milk. Tarpaulin sheets have been arranged for bedding,” said Sukanta Sikdar, Block Development Officer of Kaliachowk 3.

The school is now under constant security, guarded by armed policemen and personnel from the Rapid Action Force (RAF), who are tasked with maintaining peace and order in the volatile region.

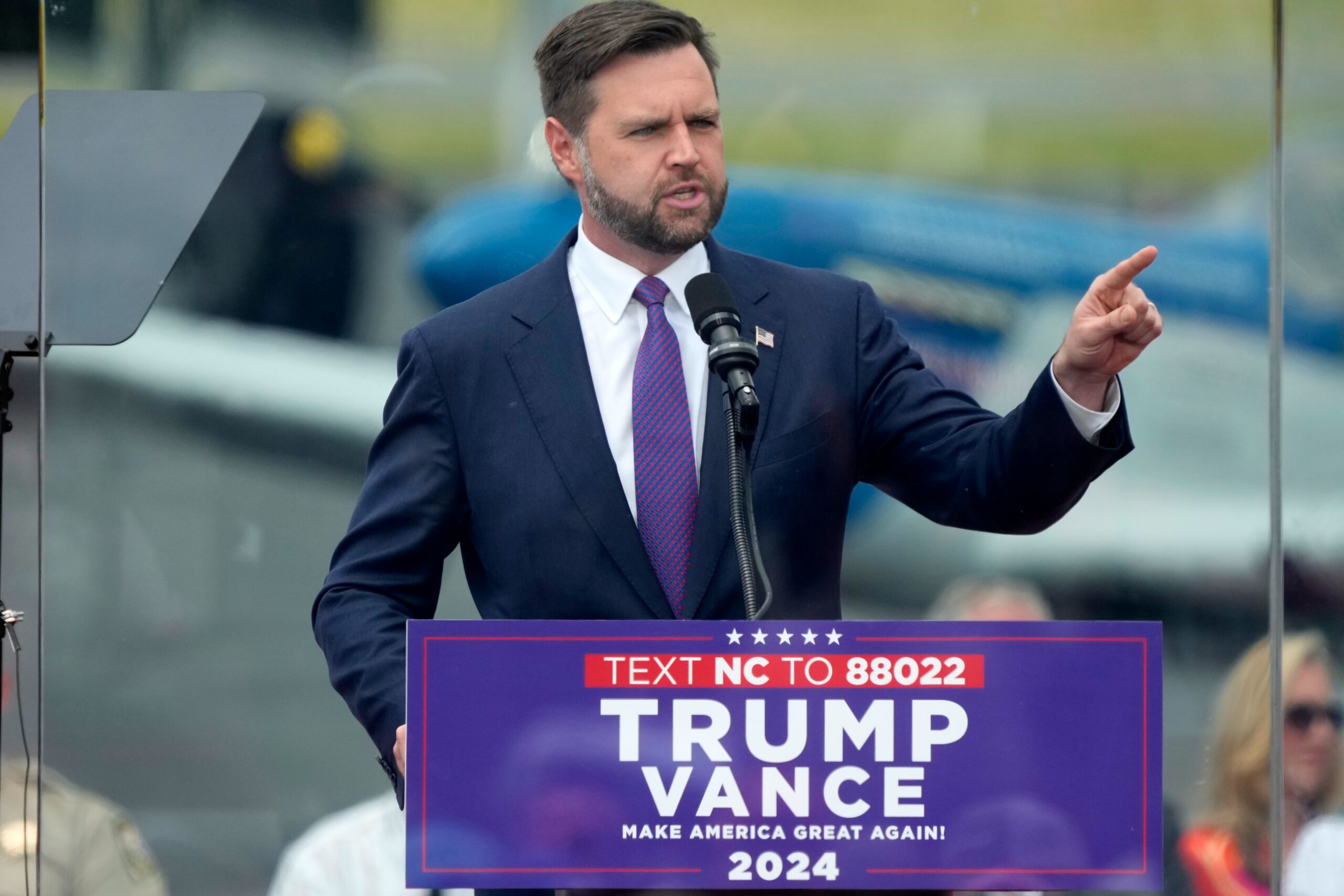

In a political development, BJP state president Sukanta Majumder visited the shelter to meet the displaced families and offer support. His visit, however, was briefly delayed as police had locked the school gates, citing security reasons and a restriction on outsider entry. After some negotiation, he was eventually allowed inside.

The emotional, physical, and psychological toll on these families is enormous. The haunting memories of violence, the uncertainty of return, and the helplessness of living as refugees in their homeland have left deep wounds.

As Saptami cradled her baby, looking around at the makeshift shelter, she said softly, “This was never our plan. All we wanted was a peaceful life in our village. Now, we don’t know what the future holds.”